Yvan Gelbart

,

Lead Analyst

Author

, Published on

October 30, 2025

No items found.

A wave of cancellations marks a new phase of rationalization in offshore wind. Our insight examines how shifting policies, economics, and developer strategies are reshaping the industry’s future pipeline.

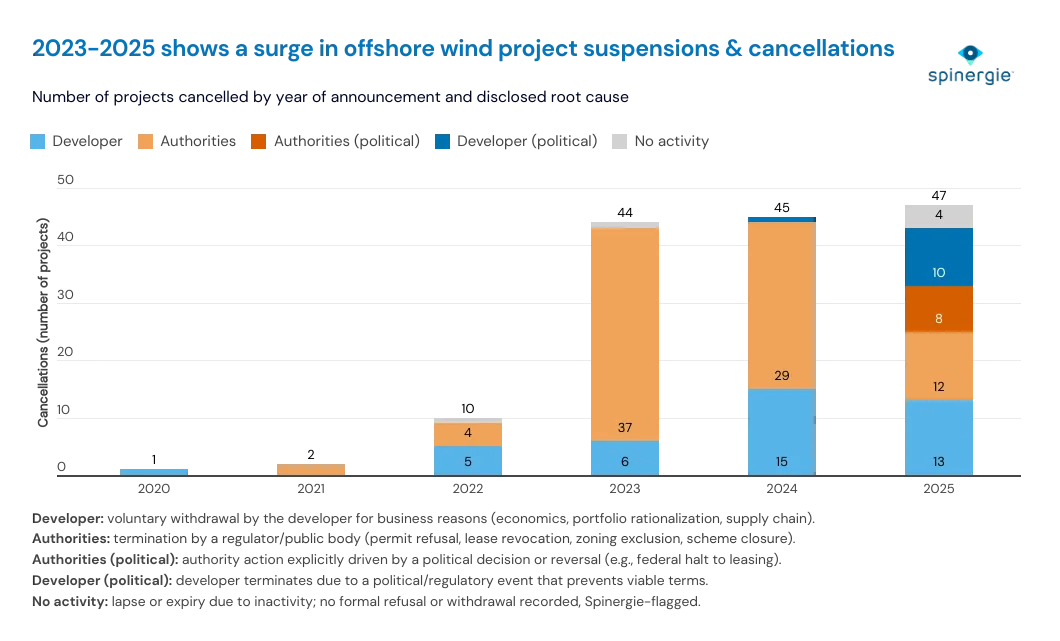

Since 2019, a total of 164 offshore wind projects have been cancelled, representing approximately 190 GW of potential capacity. Cancellations affected both early stage projects and shovel-ready projects, such as Ørsted's Ocean Wind 1 & 2 projects in the USA.

In this insight we examine the trends, causes and implications of these cancellations with these points in mind:

Offshore wind cancellations have risen dramatically in the past three years. From a negligible level in 2020-2021 despite the pandemic, the number of cancelled projects spiked in 2022 and reached unprecedented levels in 2023–2025. This trend is illustrated by a jump from just 2 projects in 2021 to over 50 in 2024. The surge is especially driven by regulatory and market upheavals in key countries.

The majority of cancellations have been driven by government and regulatory actions (“Authorities”), which account for roughly half of all cases (about 55% of total cancelled MW). Developer-initiated cancellations (due to strategy shifts or economics) make up about 20% of capacity, while policy changes halting projects, concentrated in the USA, account for ~14%.

Cancellation events in offshore wind since 2020 has been geographically concentrated in a few regions, chiefly Northern Europe and the United States, with some representation in the Asia-Pacific.

The U.S. accounts for roughly a quarter of global cancelled capacity. A majority of this comes from the 2025 federal withdrawal of unleased areas, essentially a top-down decision to halt upcoming offshore wind leasing. Apart from that, the U.S. also had many developer-led cancellations in 2023–2025 (Ørsted’s New Jersey projects, Equinor/BP’s New York projects, RWE’s cancellation of two projects in 2025, etc.) on the backdrop of the inflation crisis creating uneconomic projects. The U.S. cancellations are a combination of political/regulatory actions (federal and state) and economic challenges in executing projects.

This is the highest of any country, representing 30% of the total capacity cancelled globally. Sweden’s large figure is mainly due to the government’s rejection of numerous proposed projects in 2024 due to conflicting sea use with military zones, on the backdrop of threatening Russian presence in the Baltic, and developer withdrawals like Statkraft’s (another ~12 GW). The shift in Sweden’s geopolitical environment led to stricter permitting.

Ireland shifted its offshore wind framework to competitive auctions (the ORESS scheme) and in the process eliminated many earlier “open-door” project proposals. At the start of 2025, Irish authorities confirmed that a number of projects which had not progressed under the old system would stop. This included sizable projects like Realt na Mara (1.6 GW) and Celtic One (800 MW).

Danish cancellations are almost entirely due to the termination of the open-door scheme. Denmark’s figure includes the 20+ projects that were in that scheme and got cancelled. Denmark’s decisive policy change, driven by legal compliance with EU rules, thus shows up as a major block of authority-led cancellations in our data.

While government actions have been the primary driver of cancellations, the circumstances of developers canceling projects is key from a market perspective. Here we share some of the most impactful decisions by prominent developers and the scale of projects they have cancelled post 2020.

In June 2025, Norwegian firm Statkraft announced it would halt most of its offshore wind development efforts, leading to the cancellation of at least six Swedish projects totaling approximately 12.6 GW in early stages.

Statkraft has decided to re-focus on other energy investments amid the challenging economics of Swedish offshore wind development (Sweden lacked a subsidy mechanism at the time, and power price uncertainties were high). The company subsequently dropped bids for offshore wind in Norway and Ireland, keeping North Sea Irish Array in development with CIP.

Ørsted’s notable cancellations include Hornsea Project Four (2,400 MW in the UK), which it discontinued in 2024 after costs rose, and two projects in the U.S. totaling ~2,250 MW (Ocean Wind 1 and 2 in New Jersey). Ørsted additionally terminated offtake contracts for the smaller Skipjack 1 and 2 projects (966 MW) in Maryland in early 2024.

Ørsted's US woes were a remarkable development given the developer’s industry leadership, sending a message about cost inflation outpacing the fixed-price contracts awarded earlier. The company took substantial write-downs on these projects.

The Atlantic Shores South projects in the USA were no longer viable on awarded terms after cost inflation; partner Shell exited the JV and booked a ~$1 bn impairment; EDF booked ~€900 m impairment. Federal actions aimed to revoke part of the permitting also impacted the project.

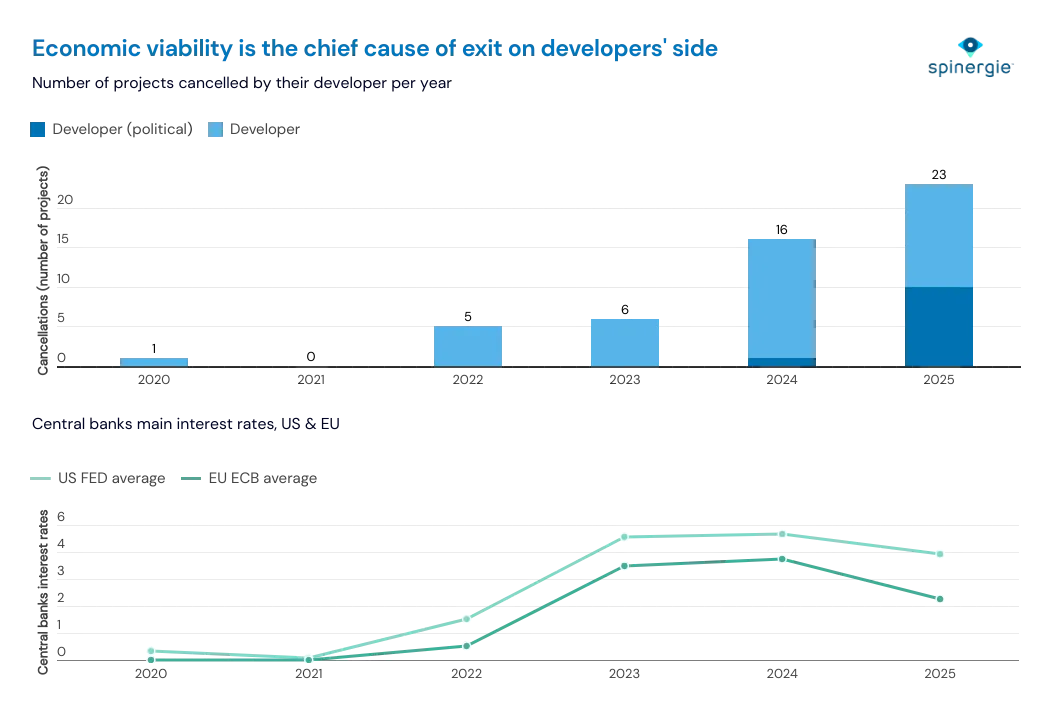

Developer-driven suspensions or cancellations have removed on the order of ~50 GW of projects, and they underscore the financial discipline being exercised in the sector. Offshore wind projects typically involve multibillion-dollar investments over a decade-long horizon. If the revenue framework (auction result or power purchase agreement) is insufficient to cover escalated costs, developers are increasingly willing to walk away, even at the expense of sunk development costs or penalties.

The inflation crisis, therefore, hit hard. Higher rates raises the cost of capital, which inflates capital recovery and breaks fixed offtake economics. Given offshore wind’s CAPEX-heavy cost structure, this pushes required strike prices well above awarded PPAs/CfDs. PPAs/ORECs contracts with no indexation suffered.

In developer-driven cancellations, non-finance related root causes exist, but are fewer once the project is officially announced. Drivers include grid connection-in-feasibility, strategic refocus (such as the case of EOLFI under Shell), and supply-chain constraints, such as Orsted's Ocean Wind projects in the USA.

In the first three quarters of 2025, 23 projects were shelved by their developers. The nature of 2025’s halts reflects significant political intervention in the offshore wind sector. Chief among these was action by the U.S. federal government: in July 2025, the U.S. Department of the Interior rescinded all remaining offshore wind leases that had not yet been awarded. This sweeping decision, following a Presidential directive in January 2025, was followed by a series of executive actions aimed at blocking offshore wind in the country (including stop work orders and revocation of permits). Many developers, already struggling to renegotiate power purchase agreements with states, pointed to insufficient regulatory support and the increased political uncertainty as causes for their exit.

The surge in cancellations since 2023 is a rationalization on the backdrop of adverse global conditions. Three structural shifts were observed:

The open-door era in the 2010s produced rapid volume and high attrition. Many proposals overlapped, conflicted with fishing or defense, or lacked grid feasibility. Countries that moved to plan-led leasing and spatial plans now publish fewer announcements, but they are more robust and cleaner: areas are screened, cumulative impacts are assessed, and conflicts are managed up front. The result is a smaller inflow of projects and a higher FID rate after award. The tracked gigawatt volume in the last few years was in part "paper capacity", but this is coming to an end as zoning corrections happen.

The main economic shock came from rates and inflation. Projects with non-indexed revenue collapsed first. Buyers are responding with index-linked CfDs, PPAs with reopeners, and clearer curtailment compensation are spreading. Where awarded terms include inflation linkage and defined renegotiation triggers, developers continue rather than exit. TSO support with scheduled grid development further reduces abandonment risk. The pipeline therefore shifts from speculative capacity to executable capacity, with a pricing architecture that tolerates a larger weight of cost variance.

Developer exits concentrate before FID. After FID, termination is exceptional because EPC contracts, supply chains, and financing lock in. Political headwinds create uncertainty but rarely break fully contracted projects. The true “gate” is pre-FID bankability.

OSV specifications are shaped by shifting global cycles and regional operating needs, with AHTS defined by power and PSVs by deck area. In this article, offshore energy analyst Eloïse Ducreux explores how these dynamics have influenced fleet design and demand across offshore markets.

UK offshore wind AR7 awarded 8.4 GW across six projects, boosting long-term CfD certainty and driving demand across the UK offshore wind supply chain.

.jpg)

Larger offshore wind projects bring both unique installation challenges and the innovative technologies used to solve them. As monopiles grow in size, the use of pile grippers increases. Spinergie’s lead analyst Yvan Gelbart, and senior offshore wind analyst Maëlig Gaborieau, explore the pile gripper market in this blog post.