Yvan Gelbart

,

Lead Analyst

Author

, Published on

December 30, 2025

No items found.

Maersk’s Sturgeon WTIV was set to be a pioneering Jones Act-compliant vessel for the US offshore wind market. Yet, with the domestic market faltering under the new administration the project was terminated just before delivery. Is this a sign of the wind market replicating the offshore rig glut of the mid-2010s? Spinergie’s Lead Analyst, Yvan Gelbart, presents his analysis.

.jpg)

In 2022, Maersk—soon to become the Maersk Offshore Wind subsidiary—ordered a purpose-built wind turbine installation vessel (WTIV) with a patented feeder system, the Sturgeon. The aim: install faster in the U.S. by keeping the WTIV offshore while Jones Act-compliant tugs and barges shuttle components from U.S. ports. The vessel would be built in Seatrium’s Singapore yard for US$475m.

Yet, on October 10, 2025, as the U.S. wind market faltered under inflation and policy drift, the project was terminated by Maersk right before delivery, leaving both the shipyard and vessel owner at odds.

The episode recalls the offshore rig glut of the mid-2010s, when ambitious newbuilds turned into stranded assets as demand collapsed. Is offshore wind now repeating that pattern of overreach—chasing a market that failed to materialize on time?

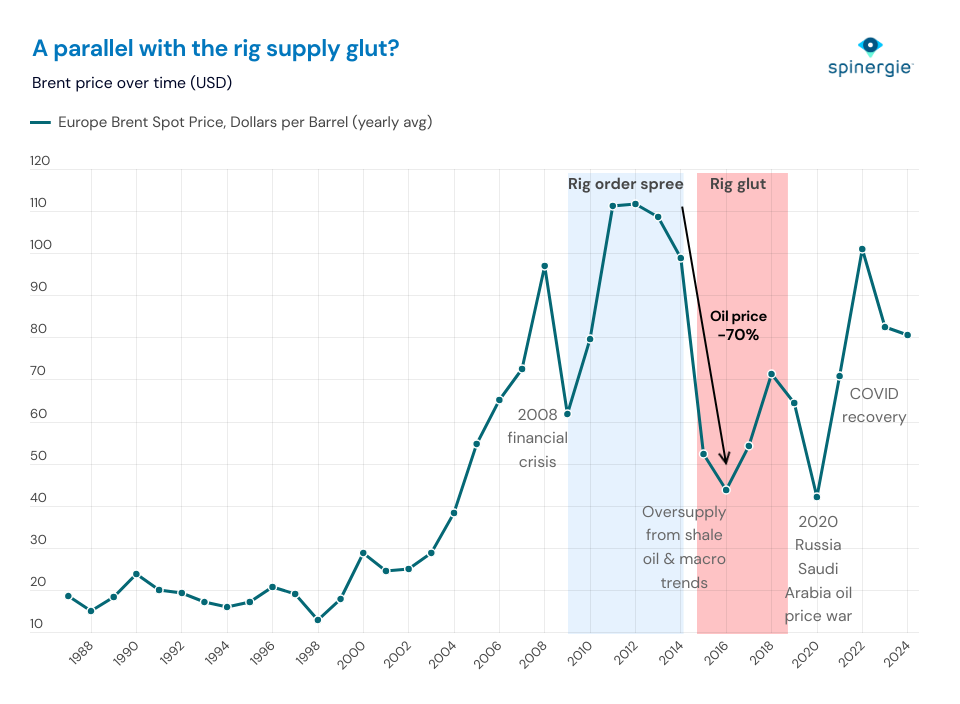

In the 2010s, the oil and gas industry was buoyed by a $100+ barrel price (Brent), which prompted drilling contractors to place many orders for new drilling rigs, expecting strong demand.

But in 2014-2015, oil prices collapsed due to international oversupply. The oil price collapse led to a brutal downturn in the offshore sector, leaving many newbuild rigs without work. Drilling contractors that had ordered rigs during the boom years suddenly faced an oversupplied market and scarce contracts.

Drilling contractors that had ordered rigs during the boom years suddenly faced an oversupplied market and scarce contracts.

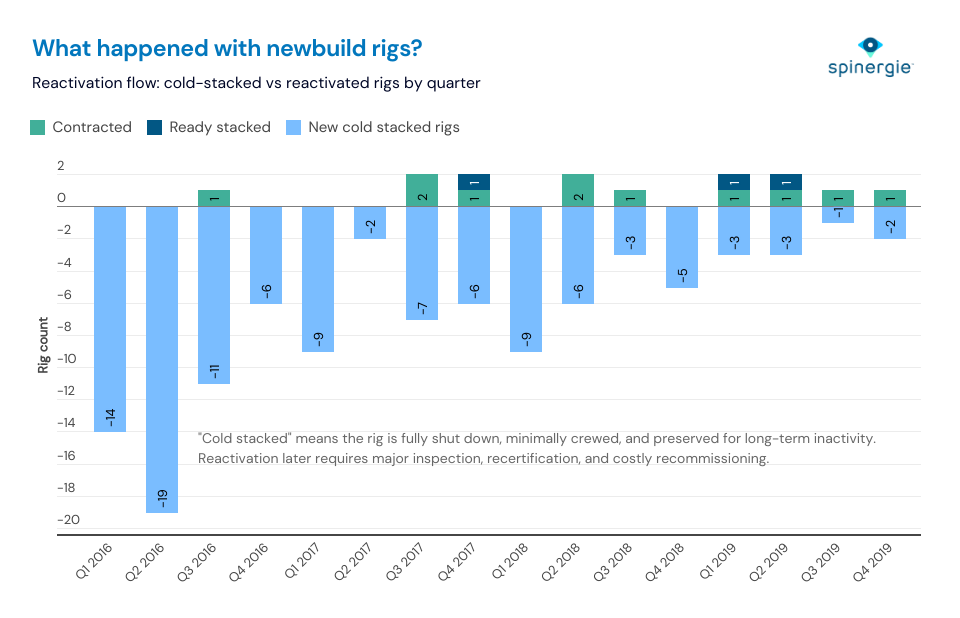

By early 2016, at least two dozen rig construction contracts had been delayed or terminated, especially at Chinese shipyards that had offered easy ordering terms. In survival mode and unable to secure jobs for these rigs, drilling contractors negotiated delivery deferrals for months or years, hoping for a market rebound. When the outlook didn’t improve, several declared shipyards in breach of contract as a legal basis to cancel orders and avoid final payment.

Because rig construction contracts are complex and cancellation rights limited, these cancellations often ended up in protracted legal disputes. Whether a contractor could walk away without penalty depended on proving the yard’s breach (e.g. missed deadlines or specs), which shipyards contested. In many cases, court proceedings ensued to determine if the cancellation was legally justified or if the contractor was simply defaulting to avoid cost.

For shipbuilders, the many contractor cancellations left dozens of rigs stranded at yards, often 90%+ complete but with no buyer.

By late 2018, oil prices had modestly recovered and the free-fall in rig demand bottomed out. The pace of cancellations slowed. As the offshore drilling cycle began to rebound in the following years, the focus turned to absorbing the cold stacked newbuilds. Many of the once-canceled rigs entered service under new owners, buying the assets at a discount.

The majority of the nearly completed units from that era did eventually enter service, albeit after a long delay and often under different ownership and financial terms. The case of Seadrill provides examples. The West Aquila and West Libra, both drillships (a floater type of drilling asset) ordered at DSME, were canceled in 2018 and later resold. Transocean acquired the West Aquila, while DSME (now Hanwha Ocean) retained West Libra. The West Mira, another Seadrill unit, had progressed to sea trials before its 2015 cancellation; it was eventually completed and entered service under Seadrill Partners after a separate ownership arrangement. Overall, most assets were finished and reallocated after years of dispute.

In the case of Maersk, Maersk Drilling had completed delivery of its floater fleet by 2014, with the Maersk Venturer and Maersk Voyager among the final drillships to enter service, just before the market collapse. Its last jack-up, delivered in 2016, also avoided the downturn. The company had no further rigs on order and, beyond rumors about acquiring a stranded unit, never sought to expand its fleet during the glut.

On the other hand, a few “white elephant” (a possession that is useless and expensive to maintain) rigs remain in yards or quaysides, unsold and rusting. The most ill-fated examples are the Awilco newbuilds: two CS60 ECO MW semisubmersibles ordered from Keppel FELS Singapore in 2018 and 2019 for about USD 425 million each. Awilco later issued termination notices citing alleged contract breaches, which Keppel firmly rejected. Both rigs have since been marketed repeatedly, without success, as their niche design deter operators.

On October 10, 2025, Maersk terminated its US$475m WTIV newbuild at Seatrium when the ship was 98.9% complete and expected to go on Empire Wind 1 for a turbine campaign. On October 20, Seatrium issued formal notice to Maersk Offshore Wind that its wind installation vessel would be ready for delivery on January 30, 2026. The following day, Maersk Offshore Wind filed a Notice of Arbitration. According to the yard, the notice stated that “disputes have arisen between the parties,” without specifying the grounds or claims sought. The word on the market reports actual delays on the shipyard’s side. The case will be heard under the London Maritime Arbitrators Association framework.

Delays or not, why cancel now? On the demand side, offshore wind project cancellations have risen dramatically in the past three years. From a negligible level in 2020-2021 despite the pandemic, the number of cancelled projects spiked in 2022 and reached unprecedented levels in 2023–2025. The demand drop is especially driven by regulatory and market upheavals in key countries, on the backdrop of global inflation rendering projects uneconomic – due to costs increase, versus a price drop in the case of the barrel.

In 2022, Maersk ordered the Sturgeon. The company, novice in offshore wind, took a massive bet on the US wind market. They ordered, as their first ever vessel, a custom WTIV with a tug and barge solution that would be racked in below the hull of the WTIV. The bespoke design would tackle a quirk specific to the US market: Jones Act, blocking components from being transported from US points by foreign built vessels, here relying on the barge to work with Jones Act.

Read More: How the feeder barge method is the key to unlocking increased offshore wind capacity in the USA

Maersk's custom design would have cut the installation time in the US by a very interesting margin (claimed ~30% productivity gain versus conventional jack-up methods) and would have been the second Jones Act compliant solution for shuttling turbines along Charybdis in a budding market.

However, the US offshore wind market failed to materialize its promises on the backdrop of global inflation, under-developed local supply chain and political uncertainty. More so, it was hit the hardest out of all budding offshore wind economies, with a political coup de grâce on the hands of the second Trump administration.

Therefore, Sturgeon no longer had reliable demand and was facing delivery at the worst possible time for its owner. The vessel’s design is solid for the American market, where the Jones Act is enforced, but not so much in the rest of the world. Maersk’s US bet proved risky.

Read More: US Wind under President Trump: the legal and practical realities of the renewables crackdown

Could we see a repeat of the drilling rigs' oversupply in offshore wind? Not exactly - while the rigs market was 800+ units strong in 2016, at the height of the glut, offshore wind has just 60 active heavy lift vessels internationally. Additionally, there are just five assets under construction: DEME’s Norse Energi, a core target of the purchase of Havfram by DEME in 2025, three newbuilds of Cadeler - which has showed no signs of stopping its fleet growth, and the new installation vessel of diversified Japanese construction firm Penta Ocean, HX118. Full list of construction and discussion stage wind installation vessels below:

Moreover, these WTIV assets are not custom: they can tackle all installation and maintenance scopes and move globally, drawing on demand in APAC, Europe, and maybe, the USAs. In addition, these assets have other uses beyond wind, namely in O&G and coastal construction jobs (DEME’s Neptune and Sea Challenger jack-ups worked nearly 500 days on a nuclear power plant two years ago). Therefore, a repeat of the rig oversupply in offshore wind is not expected—but orders have stopped until the pace of FIDs picks up again.

What happened here mirrors what was observed on the demand side: developers pulling out of emerging wind markets and abandoning techs difficult to develop, such as floating. A first-of-its-kind vessel plus a fragile demand anchor has proved a poor risk pairing.

In today’s market, delivery certainty and portfolio-level utilization matter more than concept advantages on paper. Boring is good.

If the past is mirrored, Seatrium-Maersk court claims and counter-claims over termination and damages will likely stretch over months or even years, then the vessel will be picked up, likely by a new owner when signs of robust demand are more concrete.

On the other hand, pushed by Equinor’s pressing need to build its wind farm Empire Wind 1, another solution could emerge: a third party – likely a well-established installation contractor – could bareboat charter the asset from Seatrium and execute the campaign, saving the day.

In the short term, the vessel will likely remain in the yard, like rigs did. Since the offshore energy industry tends to follow cyclic trends, a new period of strong growth will come for wind, then investors will look at readily available vessels to deploy. The question is when.

Feature image via Maersk Supply Service.

OSV specifications are shaped by shifting global cycles and regional operating needs, with AHTS defined by power and PSVs by deck area. In this article, offshore energy analyst Eloïse Ducreux explores how these dynamics have influenced fleet design and demand across offshore markets.

UK offshore wind AR7 awarded 8.4 GW across six projects, boosting long-term CfD certainty and driving demand across the UK offshore wind supply chain.

.jpg)

Larger offshore wind projects bring both unique installation challenges and the innovative technologies used to solve them. As monopiles grow in size, the use of pile grippers increases. Spinergie’s lead analyst Yvan Gelbart, and senior offshore wind analyst Maëlig Gaborieau, explore the pile gripper market in this blog post.